Electronics onboard

Another certificate in the books! 👨🎓👩🎓💡⭐

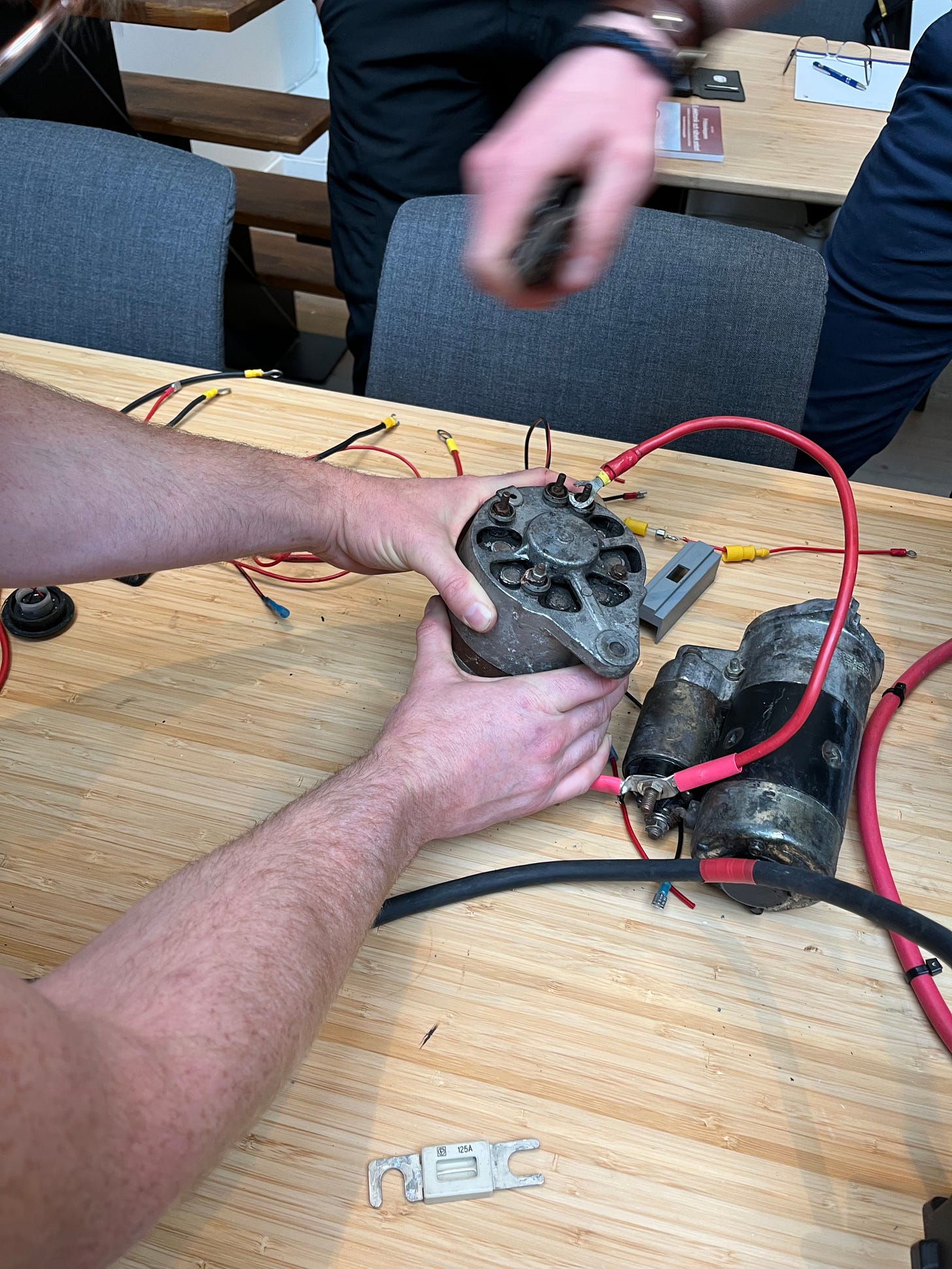

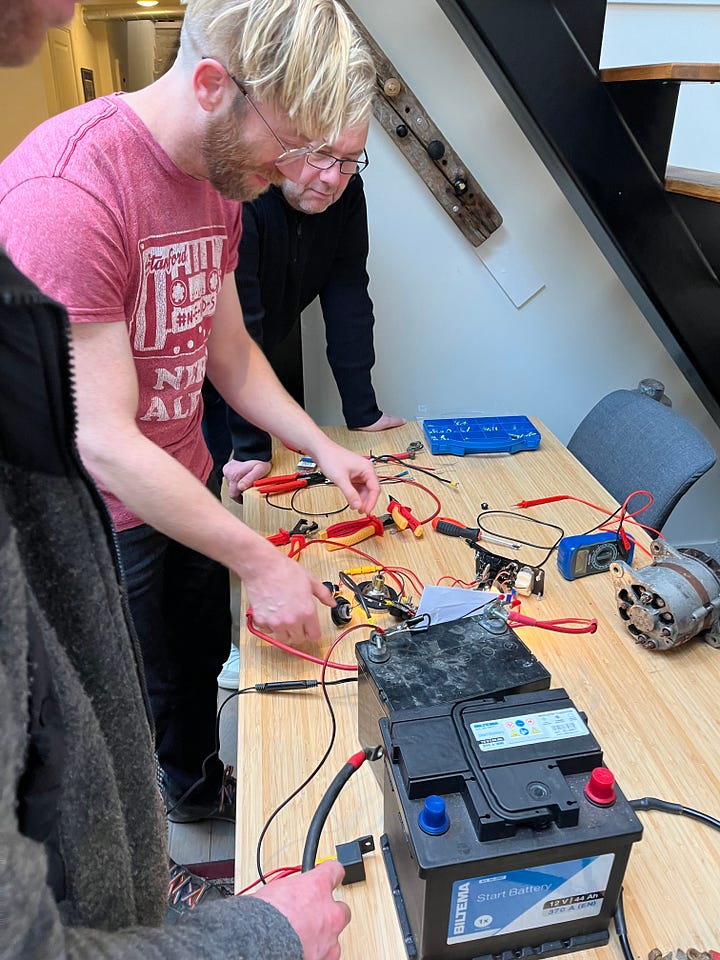

Two new electronics onboard certificate holders here! We took a 2 day weekend course at Sjöskolan in Gothenburg and both passed the test (even in its new stressful online format). Whoohoo! So we learned what to do with something like this:

Things we learned:

Electricity needs a complete circuit to work, where positive and negative are connected (for example, via a set of conductive cables, fuses and electronic devices like lamps and radios).

Most boat electricity runs on 12 volt batteries, which produce direct current (DC). These can be charged either from land power (230 AC current, needs a transformer, we’re not sure if our boat has one?) and/or onboard boat power (e.g., solar panels).

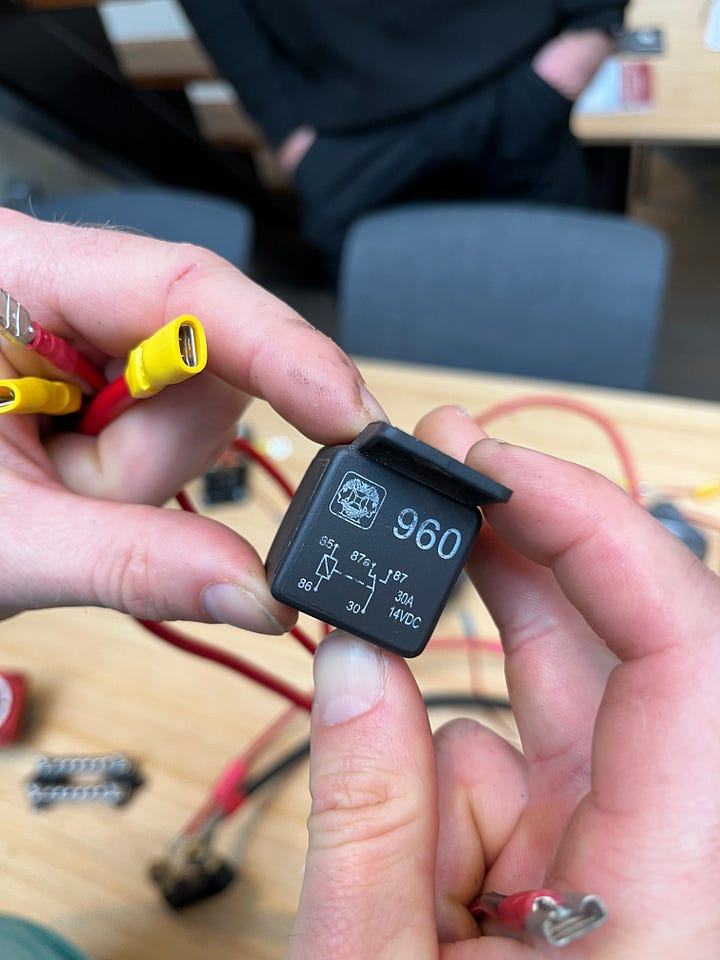

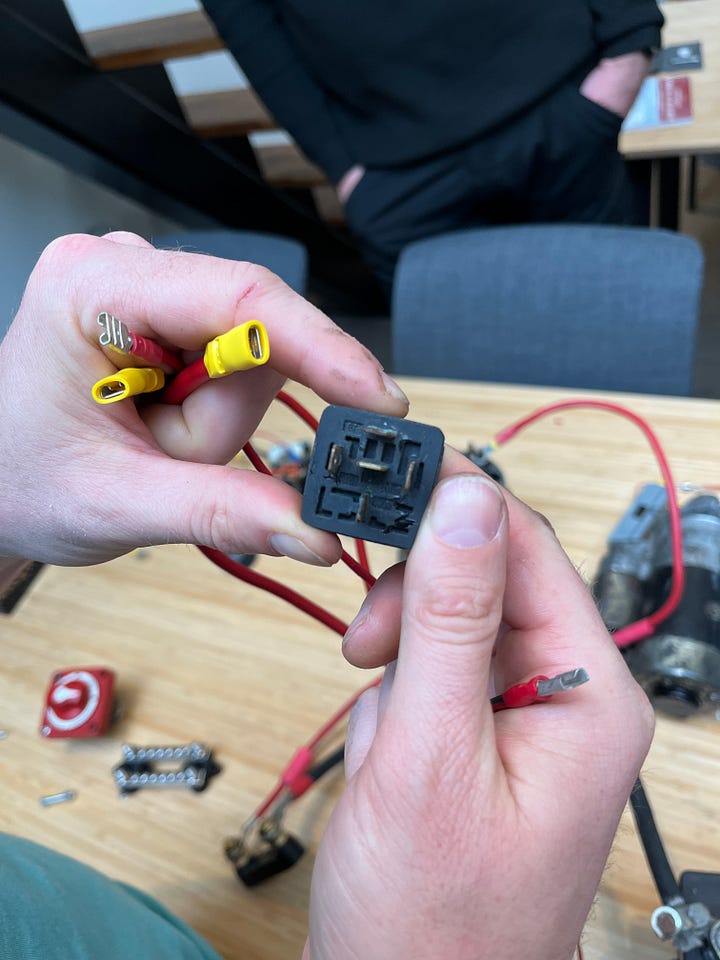

Fuses are to protect cables from overload. There should be a fuse before every device. Fuses should be sized 2x the expected current. The main fuse should be as close as possible to the battery.

Red cable for + charge, black cable for -.

Cables should be sized to the expected current. Large cables go in and out from the battery, they can get progressively smaller as they run to smaller devices. You need thicker cables if they will run longer distances, due to losses. You can look up in a table which size of cable you need.

When setting up your electrical system, sketch out the devices you want to run. Add up how much power they consume (in amps) and compare that to the battery output (e.g., 50Ah could run a 1A device for 50 hours). If your consumption exceeds your production, get more efficient (e.g., switch out old incandescent lights for LEDs, which we measured as 50x lower energy use), or produce more power (e.g., add a second battery). It’s not good for battery life to use them more than 50% (recharge after they reach half full to avoid shortening their life).

I asked “What’s the stupidest thing you can do?” The answer was, short-circuit a battery by directly connecting + and - (for example, by accidentally touching a metal wrench between them when you’re trying to attach a cable). In the worst case, this could start a fire. Have a fire extinguisher handy when working on electricity and be careful!

Get an electricity meter to be able to troubleshoot electrical systems. Set it for the right measurement in the closest unit to what you’re measuring (e.g., for a 12V battery, set at 20V instead of 2V or 200V). You will most often test the voltage, sometimes the resistance. Testing current requires moving one of the cables to a different hole- be careful.

A common cause of things not working is poor contacts. Make sure “cable feet” (not sure what that is called in English??) are well attached and not rusty. If you shake the cables a bit and get a device to work, then you need to tighten your contacts.

Simon was very happy that high school physics came into use here: Ohm’s law and Joule’s law. There are a million different ways to express them, but the one that ultimately made the most sense to me was VARWAV, which was the closest to the units things are measured in. That is:

Volts = Amps x Resistance (ohms)

Watts = Amps x Volts [yes, this means amps are in here squared]

Next step will be to investigate the current electrical setup we inherited on our boat and make sure it has all the safety elements it should, then figure out how to add a GPS this spring.